|

Grief, despite its painful nature, can reveal our resilience. It can deepen our relationships and enhance our spirituality. While it's a difficult journey, it's also an opportunity for growth and transformation. I am a bereaved mother with experiences in traumatic loss, genetic loss due to a Edward’s Syndrome, and miscarriage loss. As well, I’m a psychologist, and for the past two and half decades, I have been privileged to journey with persons integrating grief. My personal experiences, as well as those of my marriage and family, have motivated me to live in a way that celebrates life, deepens spirituality, and strengthens connections. Grief often manifests as feelings of invisibility and isolation. These experiences, while common, can act as fertile ground for a range of challenges including anxiety, depression, unprocessed guilt, inhibiting shame, distorted personal narratives, marital disconnect, impacted sexuality, and infertility, among others. While I have grappled with feelings of invisibility and isolation, they occur less frequently now. Although I have benefited from psychological resources, I have found profound comfort in spiritual practices, and I am looking forward to share this with others. Miscarriage and early infancy loss are unique forms of grief, with a myriad of potential facets. These can include medical trauma, survivor guilt, sometimes relief, confusion, spiritual questioning, depression, cultural differences, and spousal differences. Such experiences often receive minimal recognition and may not even be directly linked to the loss. Consequently, the intensity of the loss may be intensified by feelings of minimization, invisibility, and loneliness.

Why should you attend? Firstly, grief is often a topic that is avoided as discussing it can be a painful reminder of the loss experienced, and people are biologically wired to avoid pain. Secondly, in my practice, I frequently encounter concerns about potentially hurting others by bringing up the subject of loss. However, have no fear - the pain already exists and discussing the loss can help relieving it, rather than intensifying it. When we avoid it, we risk creating a deeper wound - a sense of invisibility. The purpose of this workshop is to journey together, creating a safe space where we can share and navigate the complexities of grief and its integration into our lives. Finally, I’ve heard many say, "I don’t know what to say." In the workshop, you will learn through testimony of what has been helpful, including this statement. This workshop is open to everyone. You might consider attending if you have personally experienced a miscarriage, if you know someone who has suffered a miscarriage and you're unsure how to provide support, or if you frequently interact with families and want to be equipped to handle this specific form of grief. The organizers and participants hope that through this workshop, attendees will feel affirmed, find a space to share their experiences, receive comfort, embrace the opportunity to learn, possibly adjust their narratives if needed, and cultivate a desire to support others.

0 Comments

My heart was indelibly wounded in July 2018, when my 8-year-old son Caleb died suddenly. In prayer, God has revealed that some of the wounds that I have because of this traumatic event and the aftermath are because of my own disordered expectations of myself. Shortly after Caleb died, there was a video circulating on social media about a woman whose family had been murdered, extolling her faith and the joy that she exuded despite the tragedy she had experienced. I don’t know how much time had elapsed since this woman’s tragedy, but I felt that I too should, after only a few short months, be joyful and inspiring others with my faith. Because of the expectations I had of myself, it was very hard to talk to others about my all-encompassing grief. I felt like I had nothing to offer anyone. I thought that because my grief was so big that if I shared my feelings people would not be able to handle it and they would leave, so I pushed them away. Somehow, I felt that it was better to push others away than for them to walk away. In the resulting loneliness and isolation, I learned to turn to God, spending time with Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane, in His passion and on the cross. God also brought friends into my life with whom I felt I could share a small part of my grief. They blessed me with their presence, and I blessed them with mine. In January, we celebrated Caleb’s third birthday in heaven. It was on Caleb’s birthday that God revealed to me in a particularly poignant way how He loves me (and all of us) through others. A person very dear to me, whom I had pushed away, offered my family a gift. When it was first offered, I was mortified, and I told myself that I could not accept it. I realized, through this reaction, how much I am and have been ashamed of my grief. I don’t want people to see my brokenness, even though all of us experience grief and brokenness in many ways. I wanted to be seen as healed, holy, joyful, and inspiring, and I thought that my brokenness got in the way. Yet it is in our brokenness that we find God. When we try to hide our flaws and imperfections, we are closing the door on God’s work in our lives, much like how Jesus could do little work in Nazareth because of their unbelief (Matthew 13:58). As I deliberated whether I should accept this gift, in prayer God clearly told me, “Let this person love you.” I listened to His voice and received this gift. In receiving it, I was able to encounter God and His awesome love for me. I had hardened my heart to others for so long, trying to prevent it from being hurt, trying to avoid rejection and derision because of my own pain and brokenness, but in the process, I hurt my heart more than those people ever could have. I didn’t realize how God was trying to love me through others or the wounds I had inflicted on myself because of my unreasonable and unattainable expectations. Yet because God spoke to me so clearly in the “let this person love you,” I was able to reject the temptation to refuse a gift offered in love. As I received this gift, which fulfilled much of what I was unwilling to admit that I needed, I could feel God’s all-encompassing love. While I felt assured of God’s love previously, I hadn’t realized how deeply God wanted to love me through others. For one person, it was a small act of love, but it was an all-embracing act of love from God. God demonstrated a small part of His infinite love for us all, a love that brought me peace, calm, and His personal love for me on a day that brings much anguish to this mother’s heart. Let yourself be loved, in the way He wants to love you.

“It’s like getting a hug from God!” That’s how Sharon Hagel describes the experience of receiving a hand-knitted ‘prayer shawl’. These beautiful wraps aren’t simply warm they are also imbued with prayers for the comfort and assistance of whoever ends up wrapped in their folds. So whether the recipient is a grieving widow or a sick child, they get a card explaining how they were prayed for and how God is an ever-present help in times of trouble. Hagel and a dedicated group of knitters have been meeting at the Martha Retreat Centre in Lethbridge for longer than Hagel can remember. For two hours, over six to ten weeks, they knit, pray and converse. Even when Covid restrictions limited the size of the group, they welcomed new members to this ecumenical endeavour. Hagel says, “We’re all there for the same purpose, to support the needy.” During the group’s biannual sessions many prayer shawls are completed because participants often work on knitting at home too. For Hagel it has become a regular part of her prayer life. “I sit with the Lord and I knit,” she says. “I say, OK Lord, whoever this is for, be with this person.” Many hundreds of wraps later, Hagel and the informal group of knitters continue to offer a tangible sign of God’s love to those in need of a loving embrace. A key pillar of the diocesan I Am Blessed campaign is to act decisively in aid of the needy. While most Catholics do this sporadically, a few go above and beyond. Recently, I spoke with two such women in Lethbridge who have quietly spent decades helping others by sharing their talent for knitting and crocheting. As I spoke with Sharon and Jenny, I was moved to consider how I might use my own modest talents in a pro-active way, not simply to amuse myself and my friends, but to further the coming of God’s kingdom on earth. I hope these stories might inspire others too. For over 15 years, Jenny Feher has been crocheting afghans for residents of long-term care homes. “It began when Fr. Ed Flanagan mentioned there was a need in the hospital,” Feher says. “I stopped for a while but then, after my husband died, Fr. Wilbert Chin Jon suggested I might start again. The need was still there.” Feher, a lively member of All Saints Parish in Lethbridge, prefers to work on her craft while watching TV. “If I wasn’t doing this I’d go bonkers,” she says with a laugh, “I don’t sit there feeling sorry for myself, I’m too busy counting!” Feher’s practical ministry has produced scores of colourful lap blankets over the years. Most are distributed over the Christmas season with a message of love and hope for the recipients. Visitors to local care homes can testify to how many of these striped treasures endure, and are seen tucked into wheelchairs or across bed covers. Grateful family members sometimes send thanks to the parish, never knowing who made the gift which warms their loved one. Feher is matter-of-fact about her outreach. “Everybody’s got their talents,” she says humbly while crocheting on.

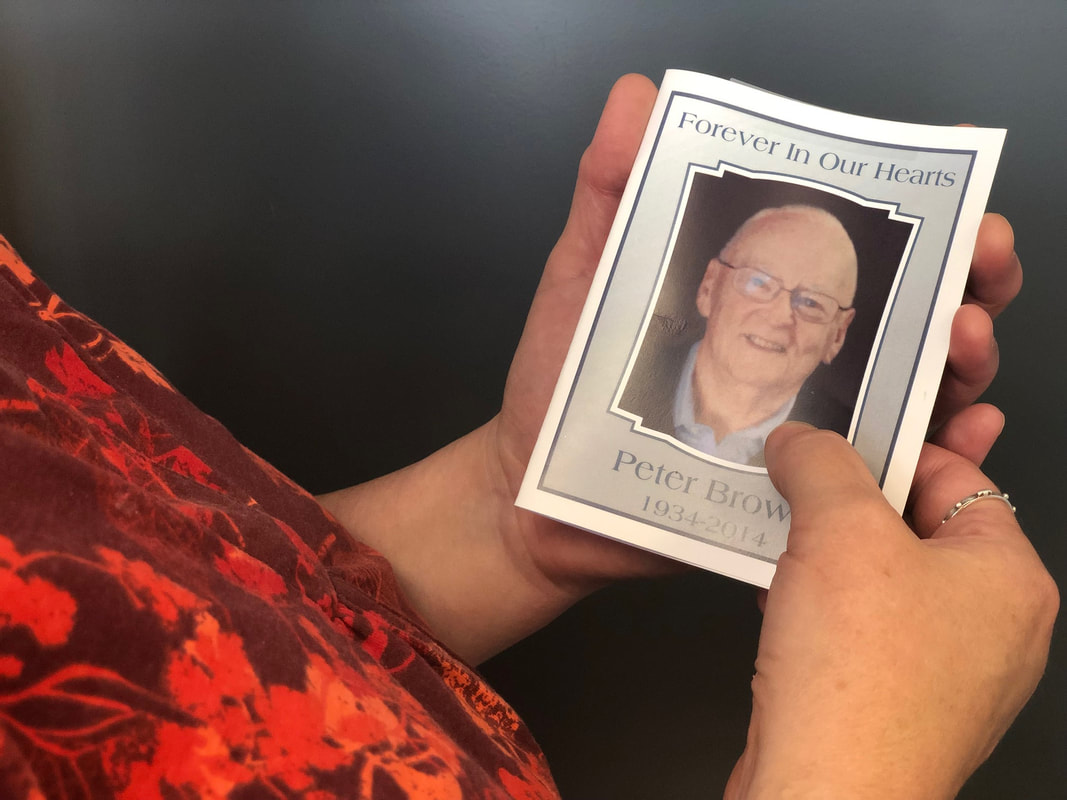

The painful truth is that I never knew my grandfather, at least in any way that a grandchild should. My grandfather went overseas to fight in the first world war, full of pride. But he returned, like so many other young men, broken in spirit. In the years after his marriage to my grandmother, life afforded him little opportunity beyond labour as a brick layer. He tried to be a man of faith, but with every bottle he drank, his sense of worth diminished. When his body finally became too tired to work, his waning years disappeared before the television screen, his mind consumed by his addiction. Whatever mercy he asked for in his final days, there is no doubt he carried tremendous pain to the grave. How many of us carry the memories of those whose stories leave us with no tale of redemption, no dramatic moment of grace to close the curtain of life, no bright ray of hope shining on their horizon. We are left sorting through the broken dreams and fractured relationships to find a goodness we can hold up, something to tell us this life meant something. During the month of November, the Church encourages the faithful to spend 30 days praying for the dead. Pope Francis has said: “Church tradition has always urged prayer for the dead, in particular by offering the celebration of the Eucharist for them: It is the best spiritual help that we can give to their souls, particularly to the most abandoned ones.” It is in the words of his predecessor, Benedict XVI, where I find great hope in the gift of purgatory, the time when God purifies those souls who long to know the peace of His eternal presence, but still carry the scars and sin of this life on earth. Benedict XVI offers these words for us: Purgatory basically means that God can put the pieces back together again. That he can cleanse us in such a way that we are able to be with him and can stand there in the fullness of life. Purgatory strips off from one person what is unbearable and from another the inability to bear certain things, so that in each of them a pure heart is revealed, and we can see that we all belong together in one enormous symphony of being.” My grandfather lost a part of his soul on the battlefields. In this month to come, I will be praying that God, even now, is putting the pieces back together again, through His holy fire cleansing and making my grandfather whole in spirit, so he can at last rest eternally at peace in the presence of our Holy God. And for my own penance, for the times I have walked by the broken and depressed, and have not thought to share the hope found in Christ’s redemption, I will give alms this month in support of veterans who are still living through the trauma of war for the sake of my freedom. Have mercy on us all, O Lord, and lead us safely Home. Written by Lance Dixon, Director of Campus Ministry at St. Mary's University

I couldn’t go into labour without acknowledging that we are a family with six children. I am so grateful for each of my babies; each one an unmerited gift. Life after loss is incredibly humbling. I thought my womb was the safest place on Earth. I thought I was good at having babies. I thought miscarriage happens… to other people. What value did Jude’s short life hold, or my own? I pondered these and countless other thoughts. I kept coming back to these words: “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness. I will all the more gladly boast of my weaknesses, that the power of Christ may rest upon me. For the sake of Christ, then, I am content with weaknesses, insults, hardships, persecutions, and calamities; for when I am weak, then I am made strong.” Corinthians 12:9-10. And in my weakness, I was met with many new and old consoling friends. To my friends still looking for a husband or wife and wanting to start a family. To my friends who silently struggle with infertility. To my friends who’ve experienced miscarriage, stillborn or infant loss, loss of a child to sickness, suicide, an accident and other kinds of loss. Thank you for opening your hearts to me this past year. Our family and friends loved us back to life with each act of kindness. Pregnancy after loss is incredibly humbling. I carried distrust of my body and anxiety throughout this pregnancy. I am grateful for the ways my eyes have been opened to the world of hidden suffering. Nearly a year later, Jude continues to come into my life in the most unexpected moments. I am still his mother and he my son. And he continues to transform my interior life and turn my gaze from ground-level to the glory of God. As most of us know by now, life isn’t as it appears in a nicely lit, staged snapshot. But it’s good to let our lights shine and to celebrate the joy that triumphs over the woundedness and pain we each uniquely experience throughout life. Here’s to this final stretch of pregnancy (due date Oct. 6). Praying for a safe labour, blessed birth and all the unfolding of life that is to follow! Written by: Sara Francis

“You do not have to be Catholic to be interred here, but most are,” says Deacon Paul Kennedy, who manages the columbaria at Sacred Heart. Kennedy knows that many Catholics are uncertain about what the Church teaches about cremation. And that’s why he takes his job so seriously. Kennedy knows what the Church teaches. He is also convinced that many who visit Sacred Heart’s columbaria will leave with a new understanding of why a growing number of Catholics will choose cremation—and a columbarium—in the years to come. Catholic teaching According to information from the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, the Roman Catholic church lifted its prohibition against cremation in 1963. Twenty years later, the option was coded in canon law. Over time, Christian Funeral Rites were altered to set the parameters for when cremation can take place before a Funeral Liturgy. The rites detail where cremated remains are placed during the Funeral Liturgy (never on or immediately in front of the altar). They also spell out the need for all of the cremains to be placed in a secure vessel. Fr. Edmund Vargas, a former pastor at Sacred Heart, first talked to Kennedy about establishing a columbarium in 2005. When the first of the 3,000 niches went on sale about five years later, the church-based facility was one of the first—and possibly the first—in Canada. Then-Bishop Fred Henry blessed the first columbarium at Sacred Heart on May 13, 2011, with the first interment that same month. The second columbarium opened in 2013. Accessible by elevator and stairs, visitors enter the columbaria through a locked door. Mourners receive a punch key code that allows them to visit the indoor space 364 days of the year. “The only day we are closed is Boxing Day. I know some people come here every day to spend time with their memories,” notes Kennedy. “On the second Saturday of each month, we also host a special memorial service in the church. Those are always well-attended, and many people visit the columbaria after that mass.” A sacred space The hallways inside the columbaria are adorned with 13 stained-glass windows. Purchased from a Catholic church in Buffalo, New York, the 150-year-old windows were painstakingly restored and framed. “We’ve backlit the windows, and the effect is beautiful. Visitors feel like they are walking past actual windows. You lose any sense that you are in a basement,” explains Kennedy. Once inside, visitors can rest on comfortable benches upholstered in an elegant shade of burgundy. Recessed ceiling lights contribute to the calming hue of the muted-yellow walls and ceilings. A lack of adornment inside the columbaria keeps eyes drawn to the niches. “Father Edmund chose very meaningful names for the columbaria,” adds Kennedy. The first columbarium is called the Holy Land, and its sections are named after Holy Land locales, like Bethlehem and Mount Herman. The Galilee section includes smaller areas named Grace, Hope, Joy, Peace and Serenity. A special section in the Serenity area holds the cremains of stillborn babies and others who died soon after birth. Most of the niches in the Holy Land are single niches, “but people can reserve two single niches, side-by-side, as long as they are available,” says Kennedy. The second columbarium, with more niches designed for two or four urns, is named Holy See. Each of its sections references a Holy See location. Again, families can purchase several niches in an area. Learn more People interested in touring the columbaria can reach out to Kennedy at Sacred Heart. He’s also available to speak with groups, including parish-based groups like the Knights of Columbus and Catholic Women’s League. Those interested will receive an Estate Planning Guide from a Catholic Perspective. “People have a lot of questions, and I’m here to answer them,” says Kennedy, who’s already secured a Sacred Heart niche for he and his wife. While he’s learned not to guess what questions people will bring to their first conversations about the columbaria, Kennedy’s accustomed to how the meetings end. “There is comfort in knowing what will happen after you die. After people choose a niche, their response is typically the same. They tell me, ‘I feel relieved.’”

From the day my Father, Theodore was brutally and callously murdered in Toronto, on Easter Monday, March 27, 1978, I wanted to meet his killer. I wanted to know how it was possible to do such a horrific thing. I wanted to know how he felt about destroying the lives of so many; my family’s, and his own. We did meet. The meeting occurred in July of 2007. Because of reading about an award I received for my Therapeutic Writing Workshops and the publication of my books about healing, voice, and agency, he emailed me. Our meeting, our reconciliation, even those many years after that dark, dark day, was a rich blessing in my life and proved helpful for him too. The word forgiveness is one that can lead to great suffering for victims and offenders alike. Victims are told that if they do not forgive, they cannot heal. Offenders are told that if they are not forgiven, they cannot move on from the crime they have committed. Forgiveness is a loaded word, with as many understandings, expectations, and definitions as there are experiences of savage loss, savage grief, savage pain. In 2012, after too many years of thinking that my life did indeed end with my Father’s, I completed a Master’s Thesis. The title: Sawbonna-Justice as Lived-Experience. Sawbonna means shared-humanity. It also means I see you, you see me. Sawbonna means that no one is better in the eyes of God. It means that we are good, bad, ugly, amazing, loved, loving, and free. Free to know that whether we can forgive or are forgiven by another human being, we are deeply known, cared-for, and embraced by God. A God who invites us, gently and generously directly back into our very own hearts. Hearts of love. Hearts of justice. Hearts of Sawbonna. We are seen. We each matter.

Laura Tysowski pays homage to her late role model and author of The Passion of Loving, Micheline Paré. In her letter Laura shares what she learned from the book and what she wished she told Micheline before her death. Micheline Paré worked as a Compassionate Care Consultant and as the Diocese of Calgary Pastoral Care Coordinator at Rockyview Hospital. Her message of love and hope is something we all could benefit from at a time of loss. My Dear Micheline. When we met for the first time somehow our souls locked. I was sitting in the front row and you came up to me with a smile and touched my hand and whispered in my ear "You are beautiful". It's been months since we last talked. I'll never forget the day we first met at St. Cecilia's Roman Catholic Church. It was May 17, 2018 at the Diocesan Pastoral Care Course #84. "Caring with Compassion". I sincerely apologize for not getting back to you sooner. As Benjamin Franklin once said, "Don't put off until tomorrow what you can do today. From this I learned the value of time; snatch, seize, and enjoy every moment of it. No idleness, no laziness, no procrastination: never put off till tomorrow what you can do today. I was wanting to go and have coffee with you at the Rockyview General Hospital and maybe I could volunteer with you in working with the elderly. I did complete the course, "Caring with Compassion" and now I'm an Exemplary Pastoral Minister. I have the two books titled "The Compassion of Loving" you signed and gave me during the course. I have two because I promised that I would get one signed by the Honorable Senator Dan Hayes who wrote the preface to your book "The Congruent Compassionate Approach".

There are days Annemieke Henri has to make herself leave her home in Bowness. Widowed just months ago, she knows that it’s important for her to be around other people. She knows it’s good for her to get her own groceries, attend Mass and meet up with long-time friends to golf, bowl or snowshoe, activities she enjoys. Henri also knows that her forays into the world sometimes do little to stem what can feel like a rising tide of sadness. Grief is like that. Even when you have others to grieve with, you grieve alone. Henri’s husband, the beloved Deacon Albert Henri, died August 28, 2018. Diagnosed with stage four lung cancer just 48 days earlier, “he’d never been sick before, never been in hospital,” recalls Henri. A mother and grandmother, she grieves Albert’s loss in her family. “I also grieve his loss as a deacon’s wife. We were deeply connected to the parishes of St. Bernard’s and Holy Name.” Does Henri take comfort in her faith? Absolutely. “At this point, I hope and believe that Albert is in heaven; that he is home. Without my faith, I would have been really lost.” But make no mistake; while faith gives Henri a kind of life raft, there are days—and moments in almost every day— when it doesn’t feel like the raft will hold. When grief fuels despair Peggy Tan knows what it feels like when grief fuels despair. Several years ago, Tan lost her mother and father-in-law in close proximity. “It was devastating to our family.” Struggling through the intense emotional pain, she joined a grief support group at her parish, St. Michael’s. Now known as Grief Share, the program runs for eight weeks beginning in January and September. Those who need more immediate support are linked to a companion program. “We are not counselors, but we listen. It’s good for the person who is grieving to know they are not alone,” says Tan, one of the three parishioners who coordinate grief support at St. Michael’s. While most GriefShare participants are Catholic, many begin the program angry with God. Following a Christian program developed in the U.S., GriefShare uses prayer to help participants rekindle their trust in God, says Tan. Seeking support Annemieke Henri hasn’t ruled out joining a support group in the future. For now, she seeks comfort in family and long-time friendships, including one with the widow of another deacon. She is also learning that it’s okay to sometimes want to be alone in her grief. On Christmas Day, for example, Henri took a few hours away from family to be alone. “I started fretting about that first Christmas alone way before Christmas. I took some time that day to feel that deep loss, to want it to wash over me and to feel my connection with God.” As grief is a profoundly personal experience, it’s not uncommon for people to reach out for grief support years after a loss, says Tan. “People have to be ready and the Holy Spirit will guide them.” Written by: Joy Gregory

|

Author

Catholic Pastoral Centre Staff and Guest Writers Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed