|

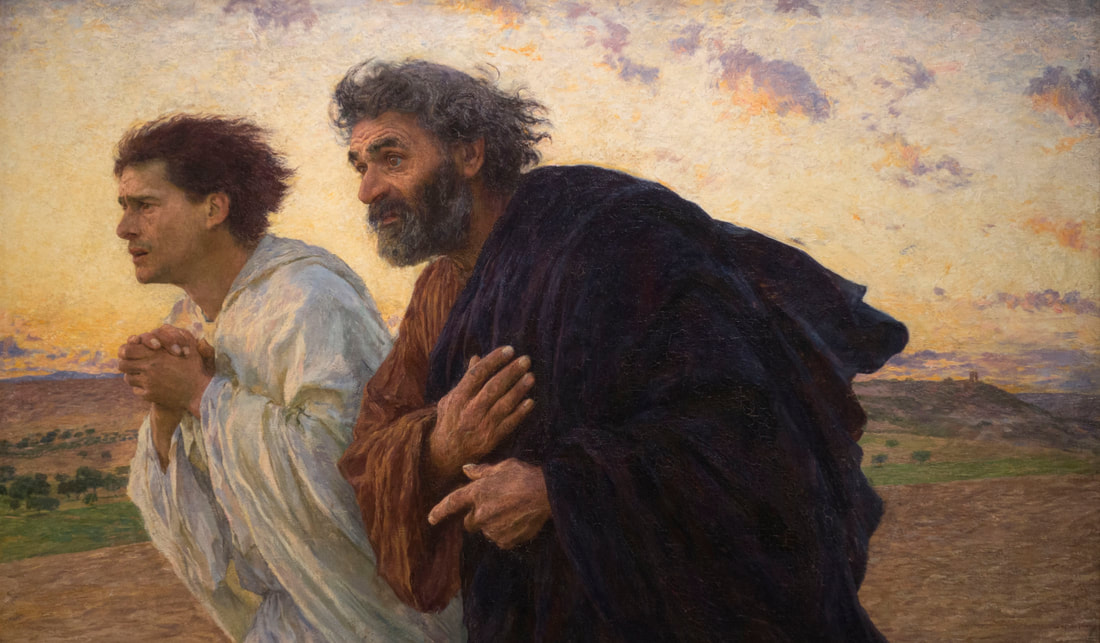

“I’m very good at Lent,” my friend confided, “but I’m not very good at Easter. I struggle with joy.” My friend said this to me after I had spent most of the day reading Catholic works from the Middle Ages as part of our diaconal formation course from St. Mary’s University. When my friend confessed her struggle with joy, St. Anthony’s severe advice was fresh in my mind: “The fibre of the soul is sound when the pleasures of the body are diminished.” St. Anthony obviously loved the desert of Lent. St. Benedict’s rule includes not seeking after pleasure, hating one’s will, remaining aloof from worldly ways, and not provoking or loving laughter. Benedict was definitely a Lent-lover. According to St. Bonaventure, the Holy Spirit whispered to St. Francis that “spiritual merchandise has its beginning in the contempt of the world,” and so St. Francis sought lonely places where he could voice groanings that could be uttered only to the Lord. It is perhaps easy to see why some philosophers call Christianity sour, dour, and humourless. More confusingly, though, these statements are hard to reconcile when considering Jesus’ comments, “Remain in my love. If you keep my commandments, you will remain in my love, just as I have kept my Father’s commandments and remain in his love. I have told you this so that my joy may be in you and your joy may be complete” (John 15: 9-12). Jesus is clear: if we keep his commandments to love one another as he loved us, to carry our cross daily, to feed his sheep, and participate in the Eucharist, we can partake in the same joy Jesus brings into the world when healing people or laying down his life for his friends. Joy should not be mistaken for a purely emotive state. Emotions are fleeting, whereas the joy Jesus describes is durable, independent of circumstance, and as much a part of what we will as what we feel. A resilient joy free from the vicissitudes of life is the only way we can make sense of comments from St. Paul that we might be “as sorrowful [as death] yet always rejoicing” (2 Cor. 6:10), or “I am overflowing with joy all the more because of our affliction” (2 Cor 7:4). The next morning, I revisited the course readings from the Medieval masters looking for evidence of this durable joy, and I found a joy grounded in our creation. St. Bernard of Clairvaux points to the foundation of joy: “it is only right to love the Author of nature first of all… we should love Him, for He has endowed us with the possibility to love.” We love God because He created love and offers us the opportunity to love, to praise, to worship, and to rejoice in His work. God’s very being is an experience of loving intimacy, and this is the ground of our inmost self, as well. Julian of Norwich adorably describes this shared identity as a process of oneing: “He knit us and oned us to Himself.” This oneing takes some effort; it takes work for Jesus’ joy to be complete in our lives. But in those rare moments when we are in harmony with Jesus and united to the Father’s will, the Holy Spirit will provide an unshakeable confidence that must be proclaimed because the only thing more wonderful than experiencing harmony with God is experiencing this oneing within a community. The Eucharist is the ultimate sharing of a commmunal presence with Jesus, and every time I accept his Body, I recall Mother Teresa’s prayerful declaration: “From now on, nothing can make us suffer or cry to the point of forgetting the joy of your resurrection!” Eucharistic participation provides a joy that is no longer just an emotion, but a permanent orientation to life itself. My Sunday Missal for the Third Sunday of Easter translates Luke 24:41 as, “While in their joy they were disbelieving and still wondering.” The Apostles were full of joy and doubt. That’s the struggle. While I have experienced moments of ecstatic joy, most of my life is comprised of ordinary moments where I “cling to the naked promise of faith,” in Henri Nouwen’s words. In dark moments, all I have to cling to is the promise that Jesus told me the truth; that if I keep his commandments, I will remain in His love and my joy will be complete. The cross protects us from a toxic positivity and a pollyannish view of life. But the cross is also the necessary means to joy, a fruit of the Spirit that, like all fruit, needs to ripen. Joy is still ripening within me, and the struggle of the Christian life is to create the ideal conditions for joy to grow.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Author

Catholic Pastoral Centre Staff and Guest Writers Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed